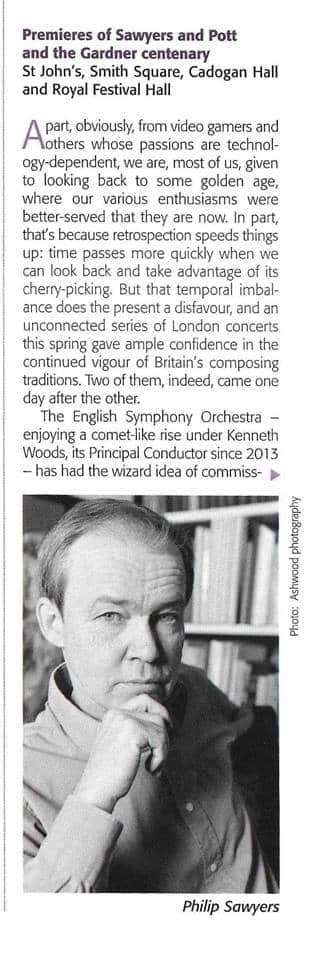

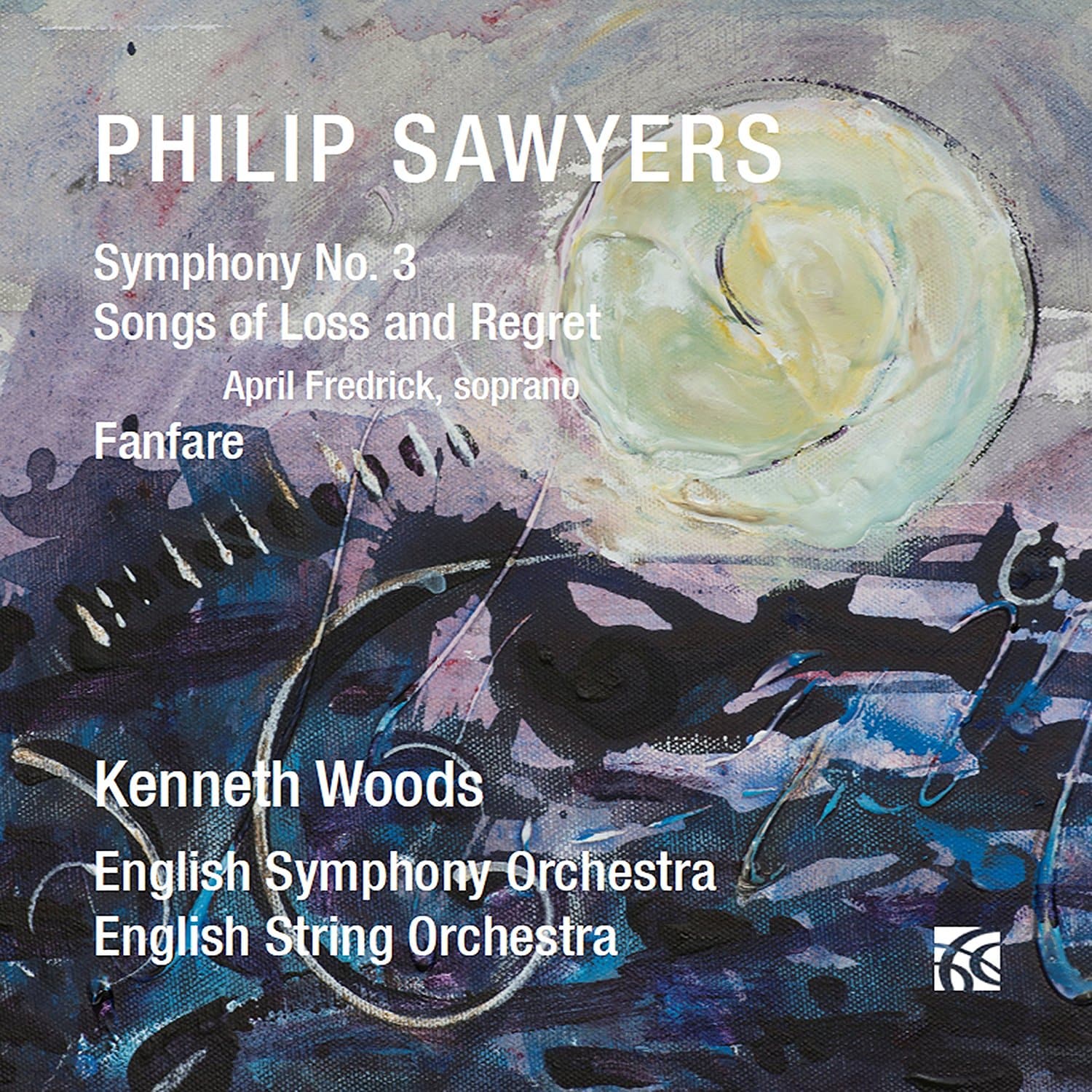

We’re delighted to note a wonderful review of Philip Sawyers‘s Third Symphony and Songs of Loss and Regret as performed at St John’s Smith Square on 28 February in the new issue of Musical Opinion – Quarterly from Martin Anderson.

Both works and the Fanfare also heard on that concert feature on our upcoming Nimbus Records recording to be released in October.

“Profundity in any art can drain you, leave you with a feeling of cathartic emptiness, and Songs of Loss and Regret left me with just that sense that I had experienced a major statement about the human condition. If it’s not a masterpiece (a word one must deploy with caution), it is at least one of the best things of its kind in a very long time….

“Robert Simpson used to talk about this or that composer speaking ‘with the breath of a symphonist’, and it was very soon clear that Sawyers was thinking on the kind of scale that would have earned Simpson’s approval. The buoyant second subject made it equally clear that his natural mode of thought is contrapuntal, and the thrilling development was a feast of imaginative and engaging counterpoint.

“….Sawyers’ Third Symphony is a tremendously impressive accomplishment. If the subsequent commissions by ‘The 21st C. Symphony Project’ turn out to be only half as good, it will still be a cause for celebration. The ESO gave this opening instalment what was obviously a zinger of a performance, Woods’ detailed direction embracing both its ambitious scale and complexity of detail; the composer, certainly, seemed dizzy with pleasure when he took his bow, and we civilians in the audience knew we had heard something special…”

Full text below:

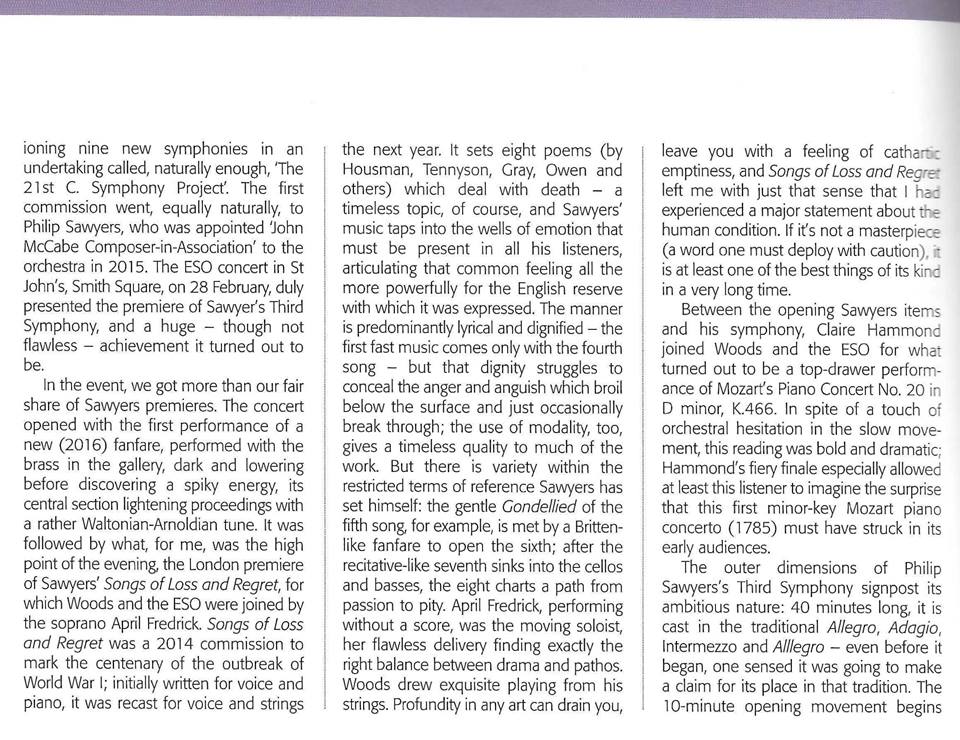

“The English Symphony Orchestra – enjoying a comet-like rise under Kenneth Woods, its Principal Conductor since 2013 – has had the wizard idea of commissioning nine new symphonies in an undertaking called, naturally enough, ‘The 21st C. Symphony Project’. The first commission went, equally naturally, to Philip Sawyers, who was appointed ‘John McCabe Composer-in-Association’ to the orchestra in 2015. The ESO concert in St John’s, Smith Square, on 28 February, duly presented the premiere of Sawyer’s Third Symphony, and a huge – though not flawless – achievement it turned out to be.

“In the event, we got more than our fair share of Sawyers premieres. The concert opened with the first performance of a new (2016) fanfare, performed with the brass in the gallery, dark and lowering before discovering a spiky energy, its central section lightening proceedings with a rather Waltonian-Arnoldian tune. It was followed by what, for me, was the high point of the evening, the London premiere of Sawyers’ Songs of Loss and Regret, for which Woods and the ESO were joined by the soprano April Fredrick. Songs of Loss and Regret was a 2014 commission to mark the centenary of the outbreak of World War I; initially written for voice and piano, it was recast for voice and strings the next year. It sets eight poems (by Housman, Tennyson, Gray, Owen and others) which deal with death – a timeless topic, of course, and Sawyers’ music taps into the wells of emotion that must be present in all his listeners, articulating that common feeling all the more powerfully for the English reserve with which it was expressed. The manner is predominantly lyrical and dignified – the first fast music comes only with the fourth song – but that dignity struggles to conceal the anger and anguish which broil below the surface and just occasionally break through; the use of modality, too, gives a timeless quality to much of the work. But there is variety within the restricted terms of reference Sawyers has set himself: the gentle Gondellied of the fifth song, for example, is met by a Britten-like fanfare to open the sixth; after the recitative-like seventh sinks into the cellos and basses, the eight charts a path from passion to pity. April Fredrick, soprano, performing without a score, was the moving soloist, her flawless delivery finding exactly the right balance between drama and pathos. Woods drew exquisite playing from his strings. Profundity in any art can drain you, leave you with a feeling of cathartic emptiness, and Songs of Loss and Regret left me with just that sense that I had experienced a major statement about the human condition. If it’s not a masterpiece (a word one must deploy with caution), it is at least one of the best things of its kind in a very long time.

“Between the opening Sawyers items and his symphony, Clare Hammondjoined Woods and the ESO for what turned out to be a top-drawer performance of Mozart’s Piano Concert No. 20 in D minor, K.466. In spite of a touch of orchestral hesitation in the slow movement, this reading was bold and dramatic; Hammond’s fiery finale especially allowed at least this listener to imagine the surprise that this first minor-key Mozart piano concerto (1785) must have struck in its early audiences.

“The outer dimensions of Philip Sawyers’s Third Symphony signpost its ambitious nature: 40 minutes long, it is cast in the traditional Allegro, Adagio, Intermezzo and Adagio – even before it began, one sensed it was going to make a claim for its place in that tradition. The 10-minute opening movement begins with a lissom melody with spreads through the strings, the quasi-fugal textures hinting at Hindemith before a sudden shake unleashes the full power of the orchestra. Robert Simpson used to talk about this or that composer speaking ‘with the breath of a symphonist’, and it was very soon clear that Sawyers was thinking on the kind of scale that would have earned Simpson’s approval. The buoyant second subject made it equally clear that his natural mode of thought is contrapuntal, and the thrilling development was a feast of imaginative and engaging counterpoint. The full-strings statement at the head of the Adagio was another link to the symphonic past (the allusion to Mahler 9 was difficult to ignore, even if it was accidental), but it was here that Sawyers both wrote the finest music in the piece and caused himself the most trouble: his material is pregnant with feeling, but he kept cross-cutting it with other ideas, preventing it from expanding, from generating and then resolving its inherent emotional crisis. Eventually a severe string statement leads to a paragraph of the utmost tragedy, a long-breathed (and long-denied) melody emerges and the strings put the music to sleep under strands of colour from solo horn, trumpet and oboe. The Intermezzo was even more of a contrast than these things usually are: this one’s of 1950s Ealing comedy stock, almost as cock-footed as Stravinsky’s circus elephants, skitting along over an oom-pah-pah bass. The finale leaps to life, in a powerful and vivid fugato – and like the first movement, it uses atonal melodic shapes in a tonal framework; here, too, the manner is vaguely suggestive of a fiercer, more angular Hindemith. A waltz-like episode briefly calms matters down before the brass suggest a passacaglia and there’s another fugal outburst, which the waltz again tries to pacify. What I suspected was the start of a brighter coda proves to be a feint; instead, there’s an imposing brass chorale, from which the pace quickens down the home strait.

“….Sawyers’ Third Symphony is a tremendously impressive accomplishment. If the subsequent commissions by ‘The 21st C. Symphony Project’ turn out to be only half as good, it will still be a cause for celebration. The ESO gave this opening instalment what was obviously a zinger of a performance, Woods’ detailed direction embracing both its ambitious scale and complexity of detail; the composer, certainly, seemed dizzy with pleasure when he took his bow, and we civilians in the audience knew we had heard something special…”