TEXTURA – November 2022

https://www.textura.org/archives/w/williams_symphonyno1.htm

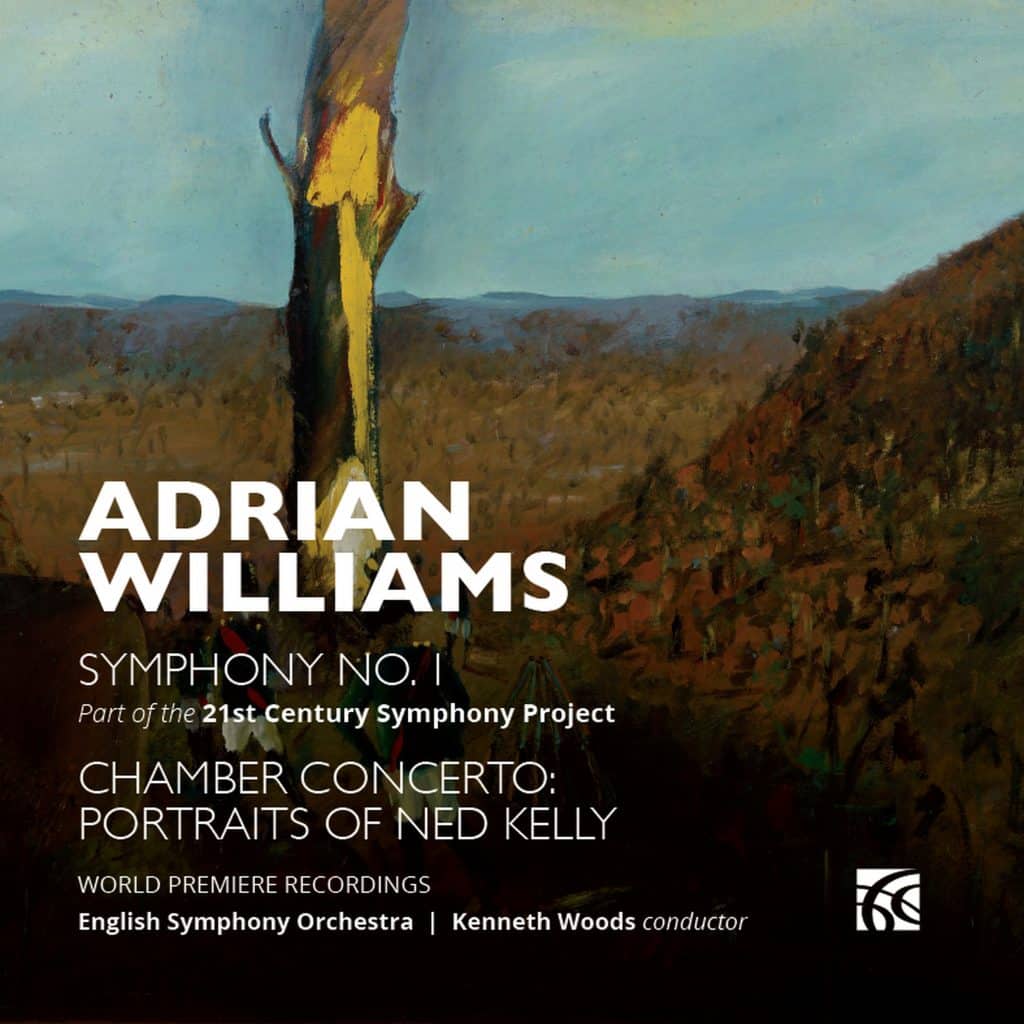

The thought of writing a first symphony must be incredibly daunting. How, one wonders, does a composer write a new one when canonic symphonies by Mahler, Sibelius, Beethoven, Bruckner, and others cast such intimidating shadows? Easing the process along for Adrian Williams (b. 1956) was a request from conductor Kenneth Woods, who asked the composer in 2018 to create a work for the English Symphony Orchestra’s 21st Century Symphony Project. Woods, the ESO’s Artistic Director, and the Worcester-based orchestra initiated the project in 2016 and have to date commissioned and issued recordings of works by Philip Sawyers, David Matthews, Matthew Taylor, and, of course, Williams, whose ESO-commissioned second symphony is in the works and scheduled to premiere in 2023.

The thought of writing a first symphony must be incredibly daunting. How, one wonders, does a composer write a new one when canonic symphonies by Mahler, Sibelius, Beethoven, Bruckner, and others cast such intimidating shadows? Easing the process along for Adrian Williams (b. 1956) was a request from conductor Kenneth Woods, who asked the composer in 2018 to create a work for the English Symphony Orchestra’s 21st Century Symphony Project. Woods, the ESO’s Artistic Director, and the Worcester-based orchestra initiated the project in 2016 and have to date commissioned and issued recordings of works by Philip Sawyers, David Matthews, Matthew Taylor, and, of course, Williams, whose ESO-commissioned second symphony is in the works and scheduled to premiere in 2023.

Staring down a blank canvas is easier when an external spur arises to push the project along, and of course it also helps when the symphony template is so well-established: even before a note’s written, the composer knows the finished piece will likely include a scherzo, adagio, and an allegro or two. In Williams’ case, his Symphony No. 1 (2020) underwent numerous tweaks until its recording took place in December 2021 at Wyastone Concert Hall in Monmouth. It’s joined on this exemplary recording by Chamber Concerto: Portraits of Ned Kelly (1998), recorded at the same location but eight months earlier. Adding to the release’s appeal, both are world premiere recordings.

Consistent with symphony form, Williams’ first frames a scherzo and slow movement with lengthy statements, the opener labeled “Maestoso – Stridente” and the closer “Energico – Dolente.” After anguished, Mahler-like strings introduce the first movement with a powerful theme, the remaining orchestral forces appear to flesh out the material and establish its dramatic, searching character. Brooding and agitated episodes intertwine, the music swelling and decompressing in turn and the ESO breathing forceful life into the music. Williams’ command of tone painting and mood building is evident throughout, as is his sensitivity to timbre. The breezy rambunctiousness of the “Scherzando” isn’t unwelcome after the drama of the opening part, though, like it, the second engages the senses with resplendent orchestral colour. Williams fashioned the third movement as an extended lament upon witnessing the devastating impact of wildfires on Australian life and habitat. The emotional response was so strong that the mournful music, which includes two extended still sections alluding to the dead forests after the fires, “wrote itself,” in his words. Churning rhythms announce the onset of the energized concluding movement, an eighteen-minute colossus that advances methodically through a variety of contrasting sections before its tumultuous conclusion. The opening movement’s string theme resurfaces during a contemplative passage, with flute and percussion amplifying the Impressionistic quality of the music. Thereafter it grows progressively more anxious, turbulent, and even explosive until the destination’s reached.

In contrast to the largely non-programmatic character of the symphony, Chamber Concerto: Portraits of Ned Kelly draws for inspiration from two things, the first, stories about the notorious outlaw who raged across Australia in the years prior to his arrest and execution in 1880, and, secondly, Williams’ friend and Welsh Borders region neighbour, Australian painter Sidney Nolan, who created a series of Kelly-related paintings that incited a musical response from Williams. While the work isn’t by-the-numbers programmatic, its spirited passages do evoke the wildness of Kelly’s life and his capture, trial, and execution (apparently, homemade body armour enabled him to be the only member of his gang to survive a final showdown with the police). A single-movement work lasting twenty-two minutes, the concerto is an adventure story told in orchestral form, with Woods’ citing of Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel as a comparative work an astute choice when both are so action-packed, wide-ranging, and imaginative. While the symphony and chamber concerto are clearly different works, both are gripping and receive sterling realizations from Woods and the ESO—no easy feat when Williams’ writing poses extraordinary challenges to the musician. That’s all the more reason, then, to imagine how delighted the composer must be with the project’s outcome.