Programme

Viktor Ullmann arr. Kenneth Woods Chamber Symphony for Strings

Hans Gál Concertino for Violin and Strings

Mieczysław Weinberg Concertino for Violin and Strings

Dmitri Shostakovich arr. Rudolf Barshai Chamber Symphony Op. 118a

Artists

English String OrchestraAbout this Concert

Shostakovich's Tenth String Quartet (Barshai’s arrangement as the Chamber Symphony Op. 118a) comes from the early years of the Brezhnev era. This deeply-personal work was dedicated to Shostakovich's closest musical confidant, the Polish-Jewish refugee composer Mieczysław Weinberg. Just as Dvořák had brought Czech elements to the Austro-German traditions, Weinberg brought the music of his heritage into the otherwise restrictive world of Soviet Realism. Hans Gál also knew the misery of exile, and, like Weinberg, experienced the indignity of detention by his adopted country when he was interned by the UK government as a so-called ‘enemy alien’ following his settlement here. The programme concludes with another transcription of a string quartet, Kenneth Woods’ acclaimed arrangement of Viktor Ullmann’s Third String Quartet, written in the Terezin detention camp near Prague where he, along with thousands of other Jews, was held by the Nazis prior to his murder in Auschwitz in October 1944.About this Concert

In 1892, Gustav Mahler completed a song based on a poem from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn) called Das himmlische Leben (The Heavenly Life). It appears at first glance to be a modest work, mostly gentle, tender and playful in character, describing a child’s view of Heaven as a land of plenty, and place of serene happiness. It is a work that seems simple, but Mahler understood that The Heavenly Life was actually one of his most profound and multi-layered compositions, and he eventually decided that it should serve as the finale of his next symphony.

Between 1892 and 1896, Mahler worked on his Third Symphony, the work which still holds pride of place as the longest symphony ever written by a major composer. Throughout this work, he threaded dozens of references to The Heavenly Life, preparing the way for the song to appear at the end of this epic journey. But it was not to be – after composing the Third’s huge Adagio, Mahler realised that, at 100 minutes, the Third Symphony was complete, and The Heavenly Life was destined to find its home in the Fourth Symphony, which he could complete four years later. Thus, this modest song was to be the focal point of Mahler’s creative life for nearly nine years.

What are the many themes in the poem which so inspired Mahler? This moving programme takes the listener on a journey that is both musical and spiritual, exploring both the composers and the ideas that influenced Mahler.

Discover More

About the Music - Viktor Ullmann arr. Kenneth Woods – Chamber Symphony opus 46a (String Quartet No. 3)

Ullmann (1898-1944), like Mahler, came from a small town, in what was then Silesia, on what is now the border of Poland and the Czech Republic. The New York Times said of Ullmann that “: “Like such other assimilated German-speaking Czech Jews as Kafka and Mahler, Ullmann lived a life of multiple estrangements.” He studied with Schoenberg and Zemlinsky, but his life took a tragic turn when he was arrested by the Nazi’s and deported to the camp at Terezin. Like his fellow composers Hans Krása, Gideon Klein and Pavel Haas, his musical activity only increased in spite of the miserable conditions, culminating in his darkly satirical opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis, or Death Takes a Holiday. His Third String Quartet was one of many of his works kept safe and smuggled out of Terizn following his deportation to Auschwitz, where Ullmann, Haas and Krása were all killed on the 17th of October, 1944.

“All that I would stress is that Theresienstadt has helped, not hindered, me in my musical work, that we certainly did not sit down by the waters of Babylon and weep, and that our desire for culture was matched by our desire for life; and I am convinced that all those who have striven, in life and in art, to wrest form from resistant matter will bear me out.’

~ Viktor Ullmann, 1944

Learn more about Viktor Ullmann at the OREL Foundation website here.

Go deeper - Explore the Score of Ullmann's Chamber Symphony with Kenneth Woods

The piece is very close to my heart- I learned it from my chamber music coach and mentor, Henry Meyer, to whom I’ve dedicated the arrangement. It will be quite a feeling to sit back and hear a great orchestra play it. Of course, the real reason I want to be there is to hear whatever terrible misprint we’ve let slip through in spite of all our late nights proofreading. Hopefully it will be something truly spectacular like the 2nd violins being written in bass clef for a page!

Meanwhile, here is the dedication page from the new score and the notes I wrote for the last performance in 2004.

PROGAM NOTE

Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944) composed his Third String Quartet in the Terezin ghetto outside Prague. The work was completed onthe 23rd of January, 1943 — a holograph of the original manuscript survived the war.

“It must be emphasized that Theresienstadt has served to enhance, not to impede, my musical activities, that by no means did we sit weeping on the banks of the waters of Babylon, and that our endeavour with respect to Arts was commensurate with our will to live. And I am convinced that all those who, in life and in art, were fighting to force form upon resisting matter, will agree with me.”

Ullmann was deported to Auschwitz on16 October 1944, in one of the last transports, where he died in the gas chamber.

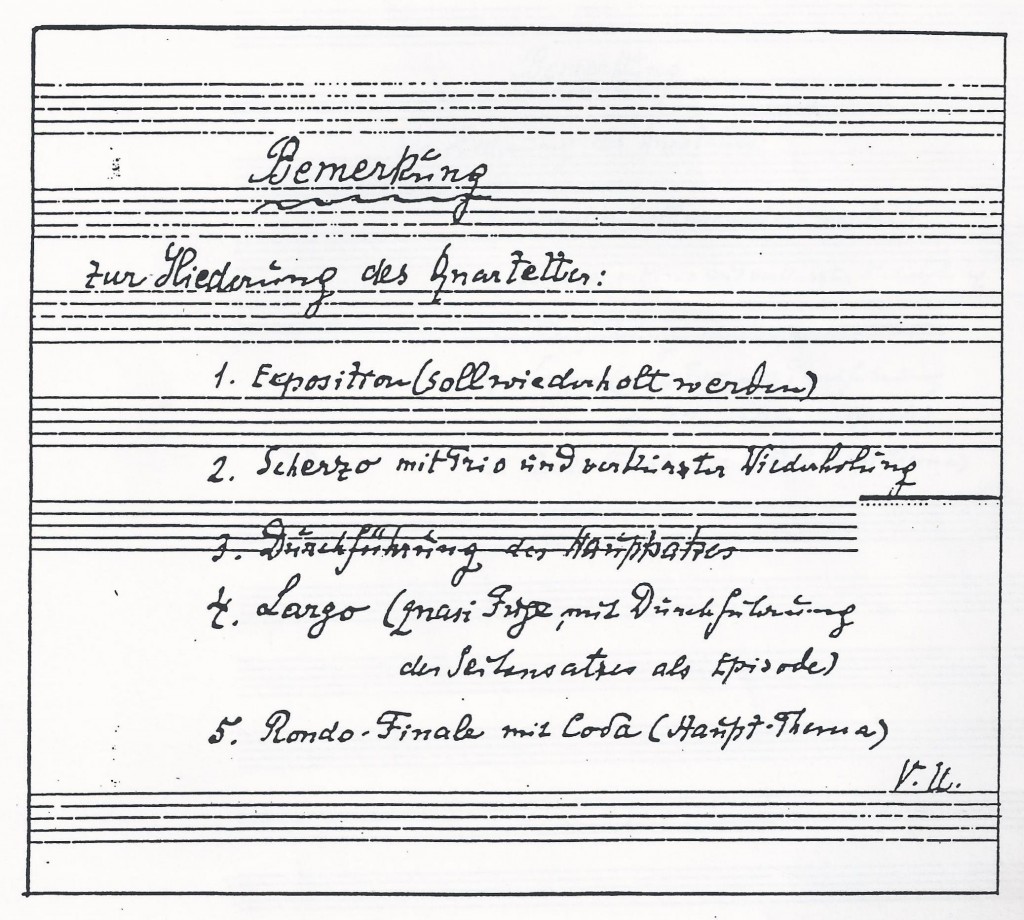

COMPOSER’S NOTE ON THE STRUCTURE OF THE WORK

1. Exposition (the repeat should be observed)

2. Scherzo with Trio and abbreviated repeat

3. Development of the first subject

4.Largo(quasi fugue, with development of the secondary subject as an episode)

5. Rondo-Finale with Coda

V.U.

ARRANGER’S NOTE

I was introduced to Viktor Ullmann’s Third String Quartet while a student at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music by my chamber music coach and mentor, Henry Meyer, the long-time second violinist of the La Salle String Quartet. Henry had been incredibly excited to learn of the work’s rediscovery, but by the time he was able to locate the score and parts, the La Salles, whose advocacy for the string quartets of the New Vienna School masters and the quartets of Zemlinsky would have made them ideal advocates for the Ullmann, had retired. “If I can’t play it, I would at least like to teach it,” he told us. We were deeply humbled and honoured by his suggestion. Henry knew all-too-well what Ullmann had faced in the camps. He himself had been interred in bothAuschwitz and Birkenau before escaping at the end of the War. I can remember coaching sessions on dazzling spring afternoons when Henry, always gregarious and witty when we worked together, would take off his jacket, exposing the serial number tattoo etched in his arm by the Nazis some fifty years earlier. The cognitive dissonance of those moments, in which shared joy in the exploration of a newly discovered masterpiece took place in the presence of visible reminders of historic horror, remains with me to this day.

I went on to perform the work often in my regular quartet, and to take it with me to many festivals. It remains a work I love to play. I began considering an arrangement of the piece for string orchestra almost as soon as I learned it. I had conducted Rudolf Barshai’s string orchestra transcriptions of Shostakovich’s Eighth and Tenth String Quartets, and Mahler’s adaptations of Beethoven’s “Serioso” Quartet and Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden,” and so I could easily imagine that the drama, violence and intensity of the Ullmann would work wonderfully with string orchestra. Likewise, Ullmann’s lyricism and coloristic genius come across equally as well in the expanded ensemble as in the original version.

Of course, the most creative aspect of such an arrangement is the creation of a double bass part. Mahler, for instance, was extremely discrete in where and how he used the double basses in his quartet transcriptions, but the art of the bass has come a long way since Mahler’s time. In making this arrangement, I was inspired by the capabilities of many of my bassist colleagues and friends, whose virtuosity concedes nothing to the finest violinists or pianists. This arrangement pre-supposes the bass player(s) will have an instrument capable of going down to a low C.

The arrangement was completed in 1999 and premiered by the Grande Ronde Symphony in February 2000.

Kenneth Woods, 2012

Program Note

Viktor Ullmann- String Quartet No. 3

(arr. for string orchestra by Kenneth Woods)

Viktor Ullmann’s String Quartet no. 3 was completed on January 18, 1943, in the final part of a career that began with him acknowledged as one of the great hopes of German musical life, and ended in his murder at the hands of racist fanatics.

In his early career, he studied and apprenticed under Schoenberg and Zemlinsky, and his early works, especially his Schoenberg Variations op 3a (1926), attracted attention throughout Europe. A passionate humanitarian with a deep interest in literature, culture and philosophy, Ullmann took a partial hiatus from composition to study the anthroposophical philosophy of Rudolf Steiner. In 1932 he and his second wife bought a bookshop in Stuttgart where they traded primarily in books on philosophy and humanism. Only months after the purchase of the bookstore, Hitler seized power and the Ullmanns fled to Prague.

In 1933 he began work on his most significant piece to date, an opera that would eventually become “The Fall of the Antichrist,” a work he completed in 1935. This masterpiece would be the crowing achievement of his prewar years, and yet it was to be the events of WW II that would spur him on to his very greatest artistic accomplishments.

Ullmann was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto outsidePraguein 1942. He was one of a handful of extraordinary creative geniuses in the ghetto, including the composers Gideon Klein, Pavel Haas and Hans Krasa. Never a particularly prolific composer in his earlier years, Ullmann composed a stunning volume of work during the two years he was in Theresienstadt, including piano sonatas, chamber music and a second opera, “The Emperor of Atlantis.”

Just hours before being deported to Auschwitz on October 16, 1944 some friends convinced him to leave his compositions behind. It is believed Viktor Ullmann was murdered in the gas chamber at Auschwitz on October 18, 1944.

‘For me Theresienstadt has been, and remains, an education in form. Previously, when one did not feel the weight and pressure of material life, because modern conveniences – those wonders of civilization – had dispelled them, it was easy to create beautiful forms. Here where matter has to be overcome through form even in daily life, where everything of an artistic nature is the very antithesis of one’s environment – here, true mastery lies in seeing, with Schiller, that the secret of the art-work lies in the eradication of matter through form: which is presumably, indeed, the mission of man altogether, not only of aesthetic man but also of ethical man.

“All that I would stress is that Theresienstadt has helped, not hindered, me in my musical work, that we certainly did not sit down by the waters of Babylon and weep, and that our desire for culture was matched by our desire for life; and I am convinced that all those who have striven, in life and in art, to wrest form from resistant matter will bear me out.’

~ Viktor Ullmann, 1944

The Third Quartet can in many ways be seen as a culmination of Ullmann’s development as a composer. In it one finds an exemplary balance of rigor and passion, a compelling formal logic, and a wealth of beautiful melodic writing. In it, he has seamlessly integrated the poetic world of vernacular music, from the waltz to the march, with the rigor of serial technique and an inspired lyrical gift. Although the work unfolds in a single musical span, its structure can easily be divided into a traditional four-movement structure where each of the four movements is linked by sophisticated motivic inter-relations.

The first movement, Allegro moderato is primarily lyrical in character and full of wonderfully luxurious harmonic writing, lightened at one point by a wonderfully waltz-like melody. The second, Presto, is ferocious and violent in much the same way as the second movement of Shostakovich’s famous Eighth Quartet. If the first movement has introduced the protagonists of our story, then the second has brought us music fit for the vilest villains. The before the third movement begins Ullmann brings back a passionate and despairing reminiscence of the first movement- what was nostalgia in the first movement is now transformed into genuine despair. The third movement, Largo, is truly the work’s heart of darkness, beginning with a fugue of desolate and unrelenting intensity. The waltz theme of the first movement here returns full of sadness.

Like the Presto before it, the character of the Rondo Finale is overwhelmingly antagonistic, violent and often terrifying, and is built from a horrific manipulation of the theme of the first movement. However, just when all is despair, Ullmann brings back the music of the first movement in the shape we first encountered it, but nostalgia replaced by defiance and regret replaced by passion. A voice of passionate defiance from within the walls of the concentration camp at midnight of humanity’s darkest hour? If ever any person wrote truly courageous music, it was surely Ullmann and this is surely that music.

c. 2004 by Kenneth Woods

About the Music - Mieczsław Weinberg – Concertino for Violin and Strings

The youngest composer in tonight’s programme, Weinberg (1919-1996) fled his native Poland in the early months of the Holocaust. Arriving as a refugee in the Soviet Union, he was the only member of his family to survive, later writing “If I consider myself marked out by the preservation of my life, then that gives me a kind of feeling that it is impossible to repay the bet, that no 24-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week creative hard labour would take me even an inch towards paying it off.” Weinberg’s tireless efforts would make him one of the most prolific symphonists of all time, surpassing the eleven by Mahler and the fifteen by his friend and mentor, Shostakovich. Like Mahler, Weinberg found a wealth of inspiration in the folk music’s of Eastern Europe, and his Concertino was withrdrawn following the notorious 1948 Soviet Composers’ Union Congress in which he was warned of excessive “cosmopolitanism”, Stalin-speak for being “too Jewish.” There is no record of this lyrical and beautiful work being performed in Weinberg’s lifetime, and it was only published in 2009.

Learn more about Mieczsław Weinberg at the OREL Foundation website here.

Video - Soloist Zoë Beyers on Playing Weinberg's Concertino for Violin and Strings

Suppressed Music and the English Symphony Orchestra

Ever since March 2013, when Kenneth Woods chose to open his very first concert as a guest conductor with the English Symphony Orchestra with Viktor Ullmann’s Chamber Symphony, the ESO has been recognised as a UK and international leader in the advocacy for, and performance of, music of the generation of composers whose music was suppressed by the Nazi’s. While there are compelling humanitarian and historical reasons for performing this repertoire, the most important reason it features so prominently in our work is that we think it is fantastic music that everyone deserves the opportunity to hear.

With this in mind, this is music that we think belongs on concert programmes year-round, not only on solemn occasions. It is music that can and should be heard not only as Suppressed Music, but simply as Great Music.

Learn more

Hans Gál escaped Nazi oppression in Mainz and Vienna, eventually fleeing to the UK. After the outbreak of World War II, he was arrested as an ‘enemy alien’ and interned in two detention centres. His memoir of this experience, Music Behind Barbed Wire, is a powerful window into the experience of Jewish refugees at the hands of their adopted homeland. Following his release, Gál settled permanently in Edinburgh, where he helped found the Edinburgh Festival and bring leading conductors and performers to the City. He was also a much-loved teacher at Edinburgh University. Given Kenneth Woods’ long association with Gál’s music, it is no surprise that his works have featured regularly on ESO concerts. Our world premiere recording of his Concertino for Cello and Strings with cellist Matthew Sharp was a MusicWeb Recording of the Year in 2017.

Mieczysław Weinberg’s music is appearing on an ESO programme for the first time in tonight’s concert, following two previous postponements and cancellations due to Covid. Weinberg fled the Nazi invasion of Poland for Russia. He was the only member of his family to survive (his immediate family were burned alive). Following the invasion of Russia, Weinberg found himself in inner exile in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, over 2000 miles from Moscow. It was Dmitri Shostakovich who arranged for Weinberg to come to Moscow, where he would settle permanently in 1943. Shostakovich and Weinberg became close friends. Weinberg continued to suffer from anti-Semitic oppression, including being denounced for “cosmopolitanism (ie Jewishness) and formalism” by Andrei Zhdanov — Stalin’s deputy with responsibilities for “ideology, culture and science” – at the 1948 Composers Congress. Later, he was arrested in January 1953 and charged with conspiring to establish a Jewish republic in the Crimea — a concoction that although absurd, was still accompanied by a death sentence. It was only through the combination of Shostakovich’s continued advocacy for his freedom and the death of Stalin in March 1953 that Weinberg was again freed.

Ernst Krenek was forced into exile and his music banned even though he was not Jewish. This was largely due to the success of his opera Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Plays On), which featured a black leading character and music inspired by jazz. We recently performed his Fantasie on themes from Jonny as part of our New Year’s concert, which ESO Digital members can see here. Over two years, we made the first complete recording of the piano concertos of Ernst Krenek with soloist Mikhail Korzhev. Those recordings were produced by Michael Haas, the producer of Decca Records groundbreaking series Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music), which first began to bring the music of this generation of composers into the mainstream. Michael now serves as Director of exil.arte Center for Banned Music, the leading Austrian research centre, archive and exhibition venue for music of this time. Volume One of the Krenek Piano Concertos (including Concertos 1-3) was a Sunday Times “Best Recording” of 2016, and Volume Two (Piano Concerto No. 4, Concerto for Two Pianos, Double Concerto for Violin and Piano and Little Concerto for Organ and Piano) was one of Forbes Magazine’s Top 11 Recordings of 2017.

Vítĕzslava Kaprálová fled the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia for France, where she died in exile at the age of 25. During her time in France, she studied composer Bohuslav Martinů, and the two eventually became lovers. It is not hyperbole to say the Kaprálová was one of the most gifted musicians of any gender to emerge in the 20th C. In her short life, she composed over fifty remarkable works, and built a ground-breaking career as a conductor of international stature long before the presence of women on the podium was considered widely acceptable. We were incredibly excited to perform her Partita for Piano and Strings with Noriko Ogawa in both Hereford Shirehall and at Kings Place as part of their Venus Unwrapped series celebrating women in music (learn more here and here). This project was recognised with an ABO Sirens aware for outstanding support of the music of historic women composers.

Bohuslav Martinů spent the last two decades of his life in exile, moving between France, America, Italy and Switzerland, all the while generating an astounding musical output as a composer. Despite being one of the more well-known figures in this list, Martinů’s enormous body of work means that there are still many gems in his catalogue that remain largely forgotten. We were most excited to discover his glorious Partita for Strings, which we performed alongside the Partita by his beloved Kaprálová in concerts in Hereford and Kings Place. Given that the ESO was founded as a string orchestra, it’s remarkable that such a tremendous work by a major figure didn’t come into our repertoire for 38 years.

In addition to Viktor Ullmann and Erwin Schulhoff, we’d like to encourage you all to explore the music of the many other important composers of this generation. There are literally thousands of works out there by dozens of composers, waiting to be played and heard again. For our part, the only thing limiting our ambition to champion this music is funding and opportunity. If the music on tonight’s programme has touched you, please think about what you can do to help make future concerts possible. This might include writing to broadcasters, presenters, festivals or funders, or making a donation or sponsoring an event. Even modest efforts can make a huge difference.